Law Commission is seeking public submissions on DNA with criminal cases. Submissions close: 31 March 2019.

DNA is a Taonga: A Customary Māori Perspective view

The aims of the consultation are to ensure that the law (Criminal Investigations (Bodily Samples) Act 1995) governing the use of DNA in criminal investigations is:

- Fit for purpose

- Constitutionally sound

- Accessible

The submissions the Law Commission receive, both in response to their issues paper and through their website, will inform their final report, which is intended to to be provided to the Minister of Justice in the latter half of 2019.

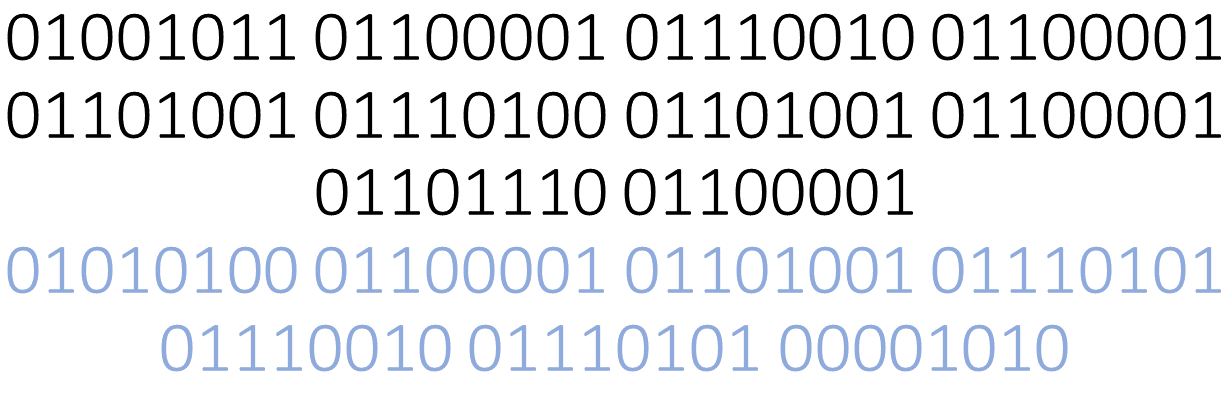

The online form is available at the bottom of the page at https://dna-consultation.lawcom.govt.nz/

The Commission begun a consultation process to identify the tikanga concepts that are engaged by the use of DNA in criminal investigations. After this initial consultation and research, the Commissions preliminary view is that personal tapu, whakapapa, whanaungatanga and manaakitanga are particularly relevant.

I am of the opinion that the primary concerns for Māori are to ensure that the law governing the use of DNA in criminal investigations is amended to:

- Acknowledge that DNA is as a Taonga

- Recognise customary knowledge rights of DNA

- Ensures DNA is stored in a tikanga appropriate and safe manner

- Ensures DNA is obtained with customary rights considered (where possible)

- Recognises Treaty of Waitangi rights with all aspects of DNA retrieval and storage.

- Ensures there are adequate Māori representation on governance and advisory groups both locally and nationally at all levels of all organisations and government who deal with DNA samples for criminal investigations and privacy.

Below are key points impacting Māori from the report.

- The review is seeking public opinion as to if the Act is current and should consider Māori.

- Criminal Investigations (Bodily Samples) Act 1995 does not consider Tikanga or the Treaty.

- Crown Law Office acknowledge the need for Māori partnerships and Treaty considerations.

- The Law Commission emphases that an important feature of any oversight regime in New Zealand will need to be providing a central role for Māori. That is because Māori are currently over-represented in the criminal justice system and are more likely to be adversely affected by use of discretionary powers, forensic DNA phenotyping, familial searching, research on the databanks and retention of biological samples and DNA profiles. In those circumstances, the Treaty principles of active protection, equity, rangatiratanga and partnership indicate that Māori should have an active role in all governance decisions.

- The Commission has four Commissioners, none of whom is tangata whenua, and currently, none of its staff identify as tangata whenua. It aims to recruit Māori staff and staff with an expertise in tikanga Māori.

- The Law Commission formed and consulted a Māori Liaison Committee convened a sub-committee to consult.

- The Commission has a Māori Liaison Committee chaired by the Hon Justice Joe Williams and include Judge Caren Fox, Judge Denise Clark, Te Ripowai Higgins, Damian Stone, Tai Ahu and Sir Hirini Mead.

- Criminal Investigations (Bodily Samples) Act 1995 which allows authorities to take DNA currently does not consider tikanga Māori, Treaty obligations or the fact that DNA is a Taonga.

- The principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, and where intrusions upon tikanga Māori and privacy are necessary for law enforcement purposes to protect and safeguard citizens in a democratic society, such intrusions are minimised.

- Known person databank – collection, those statutory collection powers are broad and discretionary. Only some of the people who qualify are required to provide a databank sample. This leaves room for inconsistency and unconscious racial bias. There is a risk that the known person databank could then exacerbate any bias by enabling more efficient policing of the people whose profiles are already on it. This is a particular concern for Māori. The Police Commissioner has acknowledged that there is unconscious bias against Māori in policing. The risk of exacerbating these issues should not be taken lightly.

- A public agency that is independent of Police and ESR should be given oversight functions in relation to the use of DNA in criminal investigations. Māori should have a central role in oversight. Oversight functions could be an extension of an existing agency’s role (such as the Privacy Commissioner), or a new agency could be created (such as a multi-disciplinary oversight committee, an advisory ethics group and/or a specialist Commissioner).

- Whether the process of obtaining reference and databank samples could be made less physically intrusive and more compliant with tikanga Māori, for instance, by introducing new sampling methods and/or alternatives to the use of reasonable force, if a person refuses to comply with a court order, notice or statutory rule requiring them to provide a sample.

- The Treaty of Waitangi is a founding document of government in New Zealand. All policy and legislative development should comply with the spirit and principles of the Treaty, both procedurally and substantively

In a 2015 report, the Waitangi Tribunal considered the principles of the Treaty in the criminal justice context in a claim about whether the Crown is acting consistently with the Treaty in relation to its action and policies to reduce disproportionate Māori reoffending rates. The Tribunal recognised and applied these principles and duties. We summarise these principles here and identify how we see these being relevant to this review.

Kāwanatanga and rangatiratanga: The Treaty is based on a fundamental exchange of kāwanatanga, or the right of the Crown to govern and make laws for the country, for the right of Māori to exercise tino rangatiratanga over their land, resources and people. Inherent in this exchange is the principle that the Crown’s right to govern is not unfettered. The guarantee of rangatiratanga requires the Crown to acknowledge Māori control over their tikanga and to manage their own affairs in a way that aligns with their customs and values. Kāwanatanga must be informed by rangatiratanga and vice versa.

To find an appropriate balance between kāwanatanga and rangatiratanga in our review it is necessary to consider tikanga Māori in respect of DNA. We introduce the tikanga concepts that we see as being particularly relevant at [2.51] of the consultation paper.

(b) Active protection: This duty requires the active protection of taonga and extends beyond the protection of specific Māori resources, to Māori interests more generally. The Crown has a duty to protect such interests as far as is reasonable in the circumstances. - For the review, it is notable that taonga can include intangible things, like values, traditions and customs. Individual people are not generally considered to be taonga, but knowledge about whakapapa (genealogy), human tissue and human genes have all been described as taonga by scholars or the Tribunal. Accordingly, to be consistent with the spirit of the Treaty, the Crown needs to actively protect the information derived from Māori DNA. This is particularly relevant in considering what the known person databank should be used for.

- Crown Law Office acknowledges that The Crown has an obligation to act fairly towards Māori and non-Māori.

- As at 30 June 2018, Māori represented 15.75 per cent of the general population but represented 41 per cent of those convicted of a criminal offence and 58 per cent of those sentenced to a prison term. Accordingly, it can be inferred that the Māori population is over-represented on DNA profile databanks as well. There are a variety of reasons for this, including racial bias in policing. A survey of police officers concluded that, while cultural awareness was improving, bias continued to be an issue for some officers.

- The Treaty reinforces the Crown’s obligation to accommodate tikanga to the fullest extent possible in the exercise of kāwanatanga;

In relation to this obligation, the Commission offered the following advice in their 2001 study paper Māori Custom and Values in New Zealand Law:

If society is truly to give effect to the promise of the Treaty of Waitangi to provide a secure place for Māori values within New Zealand society, then the commitment must be total. It must involve a real endeavour to understand what tikanga Māori is, how it is practised and applied, and how integral it is to the social, economic, cultural and political development of Māori, still encapsulated within a dominant culture in New Zealand society.However, it is critical that Māori also develop proposals which not only identify the differences between tikanga and the existing legal system, but also seek to find some common ground so that Māori development is not isolated from the rest of society. - Tikanga and Human Rights have some similarities.

- There is no oversight or auditing to ensure NZ Bill of Rights Act (NZBORA) and Treaty of Waitangi consistency in practice, nor to monitor privacy and tikanga issues. In short, the use of DNA in criminal investigations is constantly changing, and those changes are raising significant legal, ethical and tikanga issues. The Act is not able to keep up to date with the pace of these changes.

- Work has been done to consider the impact of Māori cultural values on crime scene management, particularly where a homicide is involved. Police iwi liaison officers may be appointed to give advice on tikanga, and work with iwi and whānau in investigations involving Māori.

- Identifying people by ethnicity via their DNA would likely discriminate and enhance negative stereotypes Māori, hapu and Iwi. Note: Germany, Belgium and three States in the United States, the use of forensic DNA phenotyping has been banned.

- Buccal sampling is much less physically intrusive than blood sampling. Law Commission recognises the tapu aspect of this as it uses the head.

- Should resources about DNA be made available in English and Māori?

- If, all else being equal, a Māori offender is more likely to be arrested and have a biological sample taken than a non-Māori offender, the databank will amplify this bias.

- There may arguably be benefits of a universal databank to minority groups, including Māori, because a universal databank would alleviate other disproportionate impacts of the known person databank, such as disproportionate representation, the impacts of familial searching and ethnic inferencing. However, if Police unconscious bias continues to impact on use of discretion in policing, a universal databank could enable more efficient policing of groups already disproportionately impacted by policing decisions.

- familial searching, it is reasonable to extrapolate that Māori adults are much more likely to have a close relative on the known person databank than non-Māori adults and will therefore be disproportionately affected by familial searches. Tentative calculations suggest that around 15 per cent of the Māori population aged 15 years or over have a DNA profile on the known person databank. By comparison, using the same formula, calculations suggest that only 3.4 per cent of the adult non-Māori population have a profile presence.

Links of interest

Have your say at https://dna-consultation.lawcom.govt.nz/

Dangerous game of DNA testing for Maori https://www.taiuru.co.nz/the-dangerous-game-of-dna-testing/

Leave a Reply