As opposed to conforming to Eurocentric values and academic comfort levels, this guideline is the first published bioethics guideline encapsulating traditional and modern mātauranga Māori, to explore ethical research & storage of Māori genetic samples.

This is the complete guideline with the ISBN: 978-0-9582597-8-1.

Similar to the New Zealand Health system overhaul (2022) to truly represent Māori, this guide highlights the need for a significant transformation from Eurocentric and colonised bioethics guidelines to a mātauranga Māori guideline for Māori by Māori.

Based on my unpublished PhD thesis titled ‘Māori Genetic Data – Inalienable Rights and Tikanga Sovereignty’ from Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi that I completed under the supervision of Professor Taiarahia Black of Ngāi Tūhoe, Te Whānau a Apanui, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Ngāi Te Rangi descent. It involves tens of tens of interviews and over a hundred reviewed literature items.

KO WAI AU

Pepeha is a medium by which sacred and profane knowledge is passed from one person to another regarding the speaker’s identity. It embraces charms, witticisms, figures of speech, boasts and other sayings (Williams, 1971, p. 274).

“Pepeha are used especially (but by no means exclusively) for sayings that encapsulate the boundaries or characteristics of a tribal group or region. It is etiquette to introduce yourself and it is an important part of building a sense of identity and belonging. Pepeha are essential ingredients in formal oratory, and indeed continue to be a primary means of conveying important social, cultural, legal and political principles and information” (Benton, Frame, Meredith, & Te Mātāhauariki, 2013).

Each of my iwi identified in this publication begins has a pepeha unique to that Iwi. The pepeha identify my landmarks and my whakapapa to the land, atua, kaitiaki (guardian), Taonga Species, people and to the marae.

As a researcher dealing with Māori biological samples of Taonga Species, it is important to be able to clearly identify who you are and where you come from. Without a pepeha, a researcher should not have access to any Taonga Species biological data.

Nō reira, anei ōku pepeha!

He uri au ratou: Ngāi Tahu (Koukourarata, Kāti Huirapa Rūnaka ki Puketeraki, Rāpaki, Taumutu, Ngāti Waewae, Waihao, Waihōpai, Wairewa, Hokonui), Waitaha, Kāti Mamoe, Ngāti Pāhauwera, Ngāti Rārua/Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Hikairo, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Hauiti, Ngāti Whitikaupeka.

I am a tribal descendant of the following tribes: Ngāi Tahu and 9 if its 18 tribal councils that comprise of many clans including: Koukourarata, Kāti Huirapa ki Puketeraki, Rāpaki, Taumutu, Ngāti Waewae, Waihao, Waihōpai, Wairewa, Hokonui; Waitaha, Kāti Mamoe, Ngāti Pāhauwera, Ngāti Rārua/Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Hikairo, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Hauiti, Ngāti Whitikaupeka.

Ko Makawhiu, Uruao, Tākitimu kā waka.

Ko Te Ahu Pātiki, Te Pōhue kā mauka.

Ko Kahukunu rāua ko Koukourarata kā aua.

Ko Te Arawhānui a Makawhiu, rāua ko Koukourarata kā moana.

Ko Ngāi Tūhaitara, Ngāi Tūtehuarewa, Ngāti Huikai kā hapū.

Ko Tūtehuarewa te whare.

Ko Te Pātaka o Huikai te wharekai.

Ko Te Whare Karakia Mihinare ki Puari te whare karakia.

Ko Tākitimu, Uruao, Makawhiu kā waka

Ko Te Poho o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua te mauka

Ko Ōmaru te aua

Ko Whakaraupō te moana

Ko Ngāti Wheke te hapū

Ko Te Rakiwhakaputa te Takata

Ko Te Rāpaki o Te Rakiwhakaputa te marae

Ko Wheke te whare tipuna

Ko Tākitimu te waka

Ko Nuku Mania te mauka

Ko Ōrakaia, Waikekewai, Waitatari, Waiwhio kā aua

Ko Waihora te Roto

Ko Te Kete Ika a Rakaihautū te moana

Ko Ngāti Moki rāua ko Ngāti Ruahikihiki kā hapū

Ko Ngāti Moki te whare

Ko Riki Te Mairaki Ellison te Wharekai

Ko Hone Wetere te Whare Karakia

Ko Makawhiua rāua ko Tākitimu ngā waka

Ko Maungatere te maunga

Ko Ngā Kohatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea-pokai-whenua te puke

Ko Rakahuri te Awa

Ko Ngāi Tūāhuriri te hapū

Ko Tuahiwi te marae

Ko Maahunui II te Wharenui

Ko St Stephen te Whare Karakia

Ko Uruao te waka

Ko Tuhua te maunga

Ko Arahura te awa

Ko Poutini te Moana

Ko Poutini te taniwha

Ko Ngāti Waewae rāua ko Ngāti Wairangi kā hapū

Ko Pounamu te taonga

Ko Tūhuru te whare

Ko Papakura te Wharekai

Ko Araiteuru, Tākitimu, Uruao kā waka

Ko Te Taari Te Kaumira, Kā Tapuwae o Urihia, Uretāne kā mauka

Ko Waihao te awa

Ko Wainono te roto

Ko Wainono to moana

Ko Ngāti Hateatea, Ngāi Taoka, Te Aitaka a Tapuiti, Kāti Huirapa kā hapū

Ko Tākitimu, Uruaokapuarangi, Horouta ngā waka

Ko Tākitimu te maunga

Ko Oreti rāua ko Waihopai ngā awa

Ko Te Ara a Kewa te moana

Ko Kāti Huirapa, Ngai Te Ruahikihiki, Ngai Tūāhuriri, Ngai Te Rakiamoa, Ngai Te Atawhuia ngā hapū

Ko Te Rakitauneke te whare

Ko Hine o Te Iwi te wharekai

Ko Uruao te waka

Ko Te Upoko o Tahumatā te mauka

Ko Ōkana te aua

Ko Wairewa te roto

Ko Ngāti Irakehu rāua ko Ngāti Makō kā hapū

Ko Wairewa te marae

Ko Makō te whare tipuna

Ko Te Rōpūake te whare kai

Ko Tākitimu rāua ko Uruao ngā waka

Ko Ōparure te maunga

Ko Hoka-nui, Kowhaka-ruru rāua ko Tarahau-kapiti ngā puke

Ko Mataura te awa

Ko Te Au-nui Pihapiha Kanakana te rere

Ko Ara a Kiwa te moana

Ko Maruawai te whenua

Ko Ō Te Ika Rama te marae

Ko Uruao, Te Waka a Raki, Te Wakahuruhurumanu, Te Waka o Aoraki kā waka

Ko Rākaihautū te tipuna

Ko Te Anau te Roto

Ko Waitaha te Iwi.

Ko Katirakai rāua ko Katihinekato kā hapū

Ko Kāti Mamoe te iwi.

Ko Takitimu te waka

Ko Tangitū ki te moana

Ko Maungaharuru ki uta

Ko Mōhaka te awa

Ko Raupunga rāua ko Waipapa a iwi ngā marae

I te taha o Ngāti Kura, ko Waihua te Marae

I te taha o Ngāti Paroa, ko Putere te Marae

Ko Ngāti Kape Kape, Ngāti Puraro, Ngāti Kura, Ngāti Paroa ngā hapū.

Ko Ngāti Pāhauwera te iwi

Ko Tainui te waka

Ko Pukeone rāua Ko Tuao Wharepapa ngā maunga

Ko Motueka te awa

Ko Ngāti Rārua te Iwi

Ko Niho te tipuna.

Ko Te Arawa te waka

Ko Waipa te awa

Ko Tongariro te maunga

Ko Rotoaira te moana

Ko Hikairo ki Te Rena, Ko Papakai ki Tongariro, Ko Otukou ki Huimako ngā marae

Ko Ngāti Taiuru te hapū

Ko Ngāti Hikairo te Iwi

Ko Pāpākai te marae

Ko Rākeipoho te whare

Ko Papakai, Wairehu ngā awa

Ko Rotoaira te Roto

Ko Otūkou te marae

Ko Okahukura te Whare

Ko Mangatipua, Wairehu ngā Awa

Ko Rotoaira te Roto

Ko Hauāuru te waka

Ko Tongariro te maunga

Ko Taupo Nui a Tia te Roto

Ko Tumakaurangi te whare

Ko Te Puawaitanga o Ngā Tumunako te wharekai

Ko Ngāti Tamakopiri te hapū

Ko Tūwharetoa te iwi

Ko Takitimu te waka

Ko Ruahine te Pae Maunga

Ko Rangitīkei te awa

Ko Taahuhu te marae

Te Ruku a Te Kawau te whare nui

Ko Ngāti Hauiti te iwi

Ko Ngāti Haukaha te hapū

Ko Takitimu te waka

Ko Aorangi te maunga

Ko Moawhango (Rahi) te awa

Ko Moawhango te marae

Ko Whitikaupeka te whare karakia

Ko Whitikaupeka te whare tupuna

Ko Terina te Whare Kai

Ko Ngāti Whitikaupeka te iwi

BACKGROUND

WAI 262 was brought to the Waitangi Tribunal in 1991. Part of that claim was for Māori cultural rights to genetic data of plants. Other species were not directly mentioned in the claim. WAI 262 was innovative for the time, but technology has rapidly grown in the science area over the past decade. WAI262 did not directly seek genetic ownership and recognition of the living and dead: Māori humans, endemic native species and introduced by Māori, species. Instead, WAI 262 offered a limited scope of what a Taonga Species was, relying on whānau, hapū and Iwi to decide what was a Taonga Species with several different guidelines to prove that a species is taonga, with no regard to whakapapa and mauri.

With the past 240 years of colonisation and bio prospecting, the tribunal’s definition could be used (intentionally or unintentionally) as another colonial tool to assist the removal of traditional knowledge from Māori, a weapon that could be used to say if the knowledge is not in the database, then it does not exist.

We already know that much Māori knowledge has been lost due to successful cultural assimilation lead government initiatives: Assimilation proceeds on the assumption that the integration and assimilation of the minority into the dominant majority culture is always a positive step. “Such a social philosophy is itself based upon further judgement that the dominant culture is superior to the minority culture” (Marsden & Royal, 2003, p. 133). Often minority voices and beliefs are termed by the establishment as radical, eccentric, ignorant, or even criminal to justify their oppressive assimilationist polices.

INTRODUCTION

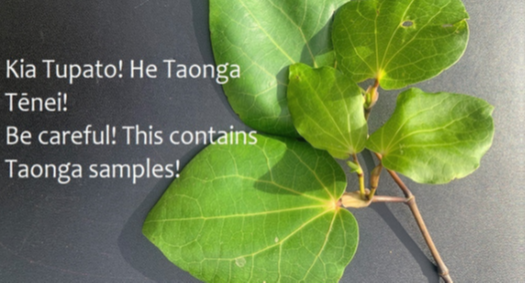

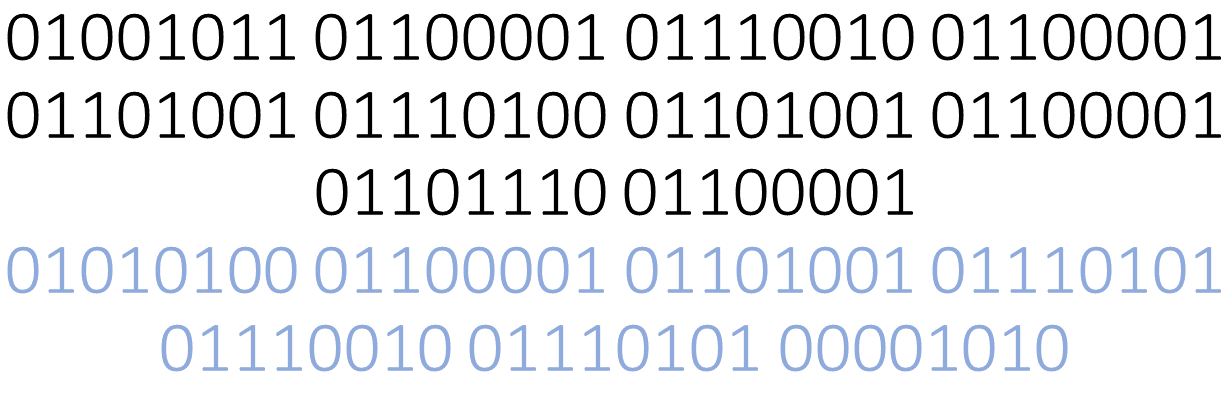

In te Ao Māori, when a person has a responsibility for whakapapa (genealogy), it is essential that the person with the responsibility is well versed in their own whakapapa. The more whakapapa connections a person can recite, the more relationships and networks that person can claim. Genetic data contains all biological data about the living specimen it was extracted from, hence it is a whakapapa.

This guideline opens with an analysis of the authors own significant and connecting pepeha[1] and marae (tribal lands and meeting house). The full pepeha can be read in the thesis. This interconnecting process is about identifying who he is, in order to sustain a Māori genetic and genomic research framework for researchers and others. The key perspective is, those who work with Māori genetic data need to understand and share their own identity, their own tikanga (customs) in order to have access, privilege, to work with Māori genetic data.

Māori genetic data is a living literary form connected to Māori and world Indigenous Knowledge systems with an abundance of knowledge to retrieve identity of place, personality, and history, to foster diverse connectivity of Māori genetic data to awaken teaching and learning passion; a vision for career opportunities and future study (Black et al., 2014).

Genetic Māori Data will grow whānau, hapū and iwi research communities and will be a major contributor to advance critical Māori scholarship as the voice of Genetic Māori Data is a forward-thinking investment strategy as it is about heritage, life aspirations, a life philosophy.

Once genomes of Taonga Species have been sequenced, Māori will have the potential ability to invest in new mātauranga Māori with the genetic data that will be used for a range of investment strategies in individuals, whānau, hapū, Iwi and Māori organisations. New partnerships with researchers will unfold unlimited benefits to everyone while supporting Māori spiritual and physical wellbeing.

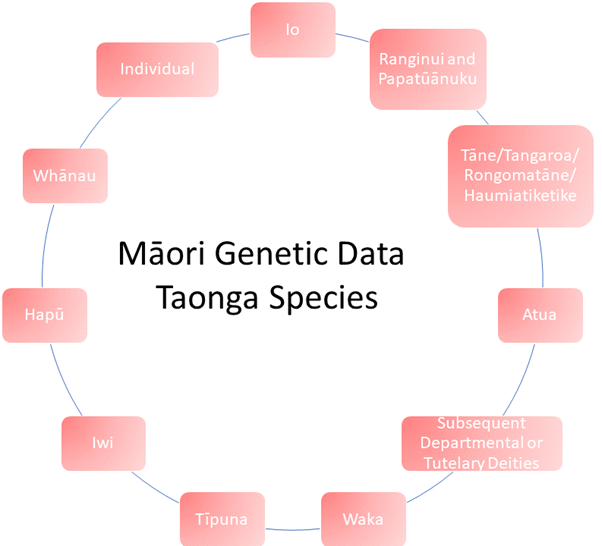

Māori Genetic Data for the purposes of this framework is genetic data that is held by Māori (collectively or individually), extracted from a Taonga Species, contains, or represents any Māori (collectively or individually) biological material that has whakapapa to a Māori deity, whether it is still in its biological state or has been altered in any way including anonymised or digitised.

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited solely from your mother, who derived it from her mother and so on back to the first mother of all Māori human beings (Hineahuone). “Geneticists have concluded by analysing Mitochondria DNA, that every person on earth right now can trace his or her lineage back to a single common female ancestor who lived around 200,000 years ago” (Cann, Stoneking, & Wilson, 1987). From a Māori perspective, this verifies that all Māori descendants are of Hineahuone.

With the human anatomy of a Māori individual, that individual is connected to Māori whakapapa which will include a connection to ancestors and deity such as Hineahuone. Therefore, the aspect of intergenerational transmission of DNA through Māori ancestry is intrinsically connected to that part of the Māori world view which has a whakapapa connection. Adding to whakapapa is tikanga. Tikanga is a powerful combined analogy of identity and cultural history engendering reflection, connection, learning and personal growth

This framework focuses on sustaining in the first instances, core Māori research resolve and excellence enabling an investigation, analysis and interpretation into, and with Māori Genetic samples. In so doing, the combined ownership for this Māori Genetic samples will reside with Māori.

There are key fundamental tikanga (customary), cultural, and intellectual expectations and property rights to support the inalienable rights of Māori and Indigenous people across the globe. Many of these interdisciplinary customary rights are explored and presented in this framework. By building upon these customary evidence-based platforms; will prove Māori have the right to protect and control the dissemination of Māori DNA, instilled with genomic ownership rights. This is based on cultural and intellectual property rights of the Indigenous Peoples of Aotearoa/New Zealand and Indigenous people across the globe.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES

Since the first colonial settlers arrived on the shores of New Zealand, Māori were taught to ignore their own epistemologies, cosmologies, and other knowledge systems in favour of a western religion and Euro centric belief systems that eradicated morals and ownership values. This resulted in the loss of significant amounts of traditional knowledge, communal living and being protectors of knowledge and nature in favour of individual property ownership. From the years 1904 to 1967 as one of the many successful government assimilation legislations, the Tohunga Suppression Act made it illegal to practice and use traditional knowledge. The results have seen significant amounts of experience, knowledge and scholarship values erased.

Numerous generations of families and individuals either lost knowledge or were institutionalised into not sharing that knowledge to the detriment of Māori. Tohuka (expert in natural lore and genealogy) of Ngāi Tahu Tiramōrehu stated that: “our ritual, that of the Māori of this land was abandoned since the coming of the faith resulting in Ngāi Tahu ignoring all these beliefs of their ancestors, however, there are many beliefs of our ancestors which can never be collected, there are so many” (Tiramōrehu, Van Ballekom, & Harlow, 1987, p. 33). This was not just confined to the South Island of New Zealand. Elsdon Best early in the 19th century expressed his concerns “the old men of Tūhoe will assert that the greatest aitua (disaster) of modern times was their forsaking the ancient beliefs, religion, customs, tapu, etc., of their race and the adaption of those of the white man. Hence the degeneration, lack of vitality and lessoned numbers of the Māori people.” (Best, 1972, p. 1014).

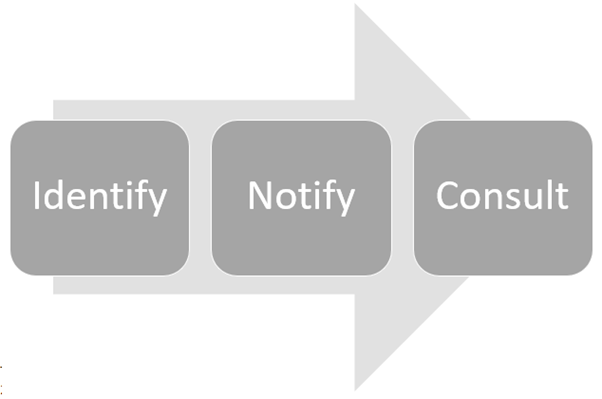

The literature reviewed at the start of undertaking this research showed four clear overlapping themes that cover all aspects of Māori ethics with gene research. The key themes identified are: Intellectual Property Rights, Tikanga Māori, Data Sovereignty and sciences. Therefore, it was identified that the primary interviewees would need to have experience, knowledge, and expertise with at least one of the key themes. The Māori interviewees in addition have expertise and be well versed in tikanga and be respected leaders in their area, discipline.

Increasingly in academia, research providers and local authorities are seeking traditional Māori knowledge to be shared, forcing Māori to take individual ownership of the traditional communally protected knowledge, and giving government and academia licence to use and own that communal knowledge. This framework has chosen to ignore those Eurocentric values, and by using Kaupapa Māori research methodologies and principles, recognise that traditional knowledge is communally protected for the next generation, so it can be used to ensure holistic health of Māori Peoples.

The research for the framework heavily utilised a Kaupapa Māori research approach utilising the five Kaupapa Māori principles by (Pihama, Cram, & Walker, 2002):

- Kaupapa Māori research gives full recognition to Māori cultural values and systems

- Kaupapa Māori research is a strategic position that challenges dominant Pākehā constructions of research

- Kaupapa Māori research determines the assumptions, values, key ideas, and priorities of research

- Kaupapa Māori research ensures that Māori maintain conceptual, methodological, and interpretive control over the research

- Kaupapa Māori research is a philosophy that guides Māori research and ensures that Tikanga Māori will be followed during the research process.

Furthermore, the core research direction utilised the following Kāti Huikai, Kāi Tūtehuarewa and Kāi Tūhaitara hapū principles ensuring that the research was completed in an Indigenous manner and not a western construct giving both the researcher and interview participants mana.

- Rakatirataka – Our leaders must be strong and act to develop self-determination for the Rūnaka. This has been exercised in the research by respecting both academia and traditional Māori values.

- Manaakitaka – We must care about our people and have empathy and respect for others’ mana. At all times, the mana of participants, colleagues and the Wānanga have been treated with respect and compassion.

- Mātauraka – We must bring confident knowledge and application of expertise towards the outcomes of the Rūnaka. Expert individuals were identified and engaged with using my own mātauraka and to seek out their mātauraka.

- Kaitiakitaka – We must work actively to protect environment, knowledge, culture, language, and resources important to the Rūnaka for future generations. A Māori world view code of ethics that will guide researchers, Māori, whānau, hapū and Iwi to be kaitiaki of their genetic data.

- Whakapapa – We must understand and acknowledge the interconnectedness of people, place, and environment. We also acknowledge whakapapa as the reason to ensure unity of purpose and outcomes for the Rūnaka. This research has identified that genetic data is whakapapa and within the research is the value of interconnectedness of Te Ao Māori whakapapa from the individual to the group, to non-human beings and then to atua.

- Tikaka – We must maintain a high degree of personal integrity aligned to the Rūnaka’s cultural protocols, understand the ever-evolving nature of tikaka and do what is right. Evolving tikaka was identified and with manaakitaka was revived and discussed.

- Whanaukataka – We must have two-way connectivity and investment in all relationships important to the Rūnaka. Whanaukataka exercised by exploring both primary and secondary sources and respecting the many knowledge holders and their interconnectedness to Te Ao Māori and mātauraka.

LITERATURE REVIEWS OF CURRENT ETHICAL FRAMEWORKS FOR WORKING WITH MĀORI GENETIC SAMPLES

This section discusses and critiques three ethical guidelines and frameworks that have been developed in New Zealand in relation to genetic and genomic research of Māori human beings’ biological samples: Te Ara Tika (Hudson, Health Research Council of New, & Pūtaiora Writing, 2010); He Tangata Kei Tua (Hudson, Beaton, et al., 2016a) and Te Mata Ira (Hudson, Russell, et al., 2016).

The three guidelines are widely referenced by non-Māori academics, but they create a deficit of tikanga Māori with genetic and genomic research, and confusion among tikanga Māori practitioners. The frameworks contain some important high-level principals, but no information about how to implement the suggestions or why there is a need for some of the tikanga. This review therefore is essential, as it will create the justification for this framework as a new body of knowledge.

To assess how useful the three frameworks are to researchers who work with Māori genetic data, a number of interviews were conducted with both Māori and non-Māori scientists who have read one, two or all of the frameworks. In addition to interviews, a survey of New Zealand Universities: Intellectual Property Policies, Research Ethics with Human Beings and Māori, Genetic Research policies were analysed for any input or guidance of any of the three frameworks including from: Victoria University [2], Lincoln University [3], Auckland University[4], Massey University[5], University of Canterbury[6] and Otago University[7].

In addition to the University policies, 74 human biological research consent forms from three Universities “University of Canterbury, University of Otago, The University of Auckland”, and the Canterbury District Health Board were analysed for references and principals from the three frameworks.

There was no proof that any of the university policies included any reference, principles, or guidelines from the three frameworks. In 73 of the 74 consent forms, there was no reference of any information from the three frameworks. Only one consent form had some principles of the three frameworks, but that consent form lacked complete protection for Māori participants.

Te Ara Tika / He Tangata Kei Tua/ Te Mata Ira Framework

Te Ara Tika Guidelines states it “is a framework for researchers and ethics committee members to support researchers to make ethical decisions with Māori human gene research”. It outlines a framework for addressing Māori ethical issues within the context of decision-making by ethics committees by bringing together various strands connecting tikanga Māori, the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori research ethics, and health research context in a way that could be understood and applied in a practical manner by researchers and ethics committees” (Hudson, Beaton, et al., 2016, p. 2).

He Tangata Kei Tua: Guidelines for Biobanking with Māori states it “is a guideline that outlines a framework for addressing Māori ethical issues within the context of biobanking with Māori tissue and to describe the cultural foundation informing ethical approaches to biobanking, to inform decision-making around ethical issues when conducting biobanking with Māori tissue and outline best practice approaches for addressing Māori ethical concerns”.

Te Mata Ira Framework, the authors claim is “designed to build on the guidance provided by Te Ara Tika because the Māori ethical issues identified in that document are relevant to all research, including genomic research”. Furthermore, the authors claim that “the framework aligns with the key principles of Te Ara Tika and considers their application to genomic research from consultation to research and post-project transformation” (Hudson, Russell, et al., 2016, p. 4). “It is the cultural foundation informing ethical approaches to genomics; to inform decision-making around ethical issues when conducting genomic research with Māori; and outline best practice approaches for addressing Māori and ethical concerns”.

This review will focus on four primary areas to ascertain what knowledge is missing from the literature:

- How relevant are the publications in 2022, considering they are now between six and twelve years and old and discuss ethics in with rapidly evolving sciences and technologies that have changed exponentially in just the past few years.

- What Kaupapa Māori research and methodologies were applied by the researchers and the extensiveness of the literature that was consulted in creating the frameworks.

- If and how a Te Ao Māori (Māori world view) perspective is applied and how that will likely be understood by Māori language speakers and Māori cultural practitioners.

- What national and international Indigenous resources and instruments that were available at the respected publication dates were utilised.

Relevance of the Literature in 2020

Gene and Genome technologies are now significantly more accessible and economic to both scientists, amateur DNA researchers and lay people than they were at the dawn of 2010 when Te Ara Tika was published. “Over the past decade, increasing resources have been poured into DNA-based research in most modern industrial countries” (Kolopenuk, 2020). For these reasons, the relevance of aging Indigenous scientific frameworks must be considered against the western scientific developments.

In 2010, geneticists were still grappling with how to make human genome sequencing a more widespread and affordable reality. Illumina advertised a genome sequencing service that cost $50,000 per person. By 2012 Direct to Consumer DNA testing became mainstream when Ancestry.com launches their new AncestryDNA Service. The U.S. Supreme Court rules that naturally occurring DNA cannot be patented in 2013. “In 2019 Veritas Genetics were offering full genome sequences for less than $600” (Grant, 2019). Now anyone can purchase DIY CRISPR genomic sequencing kits online and spend a few hundred dollars to have their DNA profile matched with direct to consumer services with a high risk to personal and family privacy” (Hendricks-Sturrup & Lu, 2019).

Te Mata Ira and He Tangata Kei Tua do not consider the access to self-genome testing and the increase of corporates who offer DNA testing that has become popular, economical, and easy to access. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing was also not available in 2010.

“By 2019, more than 26 million people — more people than in all of Australia — have shared their DNA with one of the four leading ancestry and health databases, allowing researchers to extrapolate data on virtually all Americans and raising some serious privacy concerns, according to the MIT Technology Review” (Bursztynsky, 2019). Ancestry.com claimed that “more than 15 million customers have received DNA results from them in 2019” (Ancestry.Com, 2019).

The series of frameworks offer no considerations of current or emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, racial profiling, low costs to purchase self-checking DNA tests, genetic modification, Gene Drives, online DNA web sites, Māori data sovereignty issues.

Specific issues missing from all of the publications, that largely impact Māori ; DNA and profiling, Phenotyping, familial searching, abandoned samples, or bias by the New Zealand Police with taking samples from a disproportionately higher amount of Māori than non-Māori by the New Zealand Police and other authorities (The Law Commission, 2018); the rise of Māori DNA being researched and stored in digital format by overseas researchers.

Consultation and Research

Within academia and the research world it is vitally important to be aware of all of the available literature and to cite references to give your work credibility, the ability for the reader to fact check your statements and to give credibility and authority to your claims. Without referencing other literature, the publications become personal opinions that cannot be substantiated. Moreover, in Te Ao Māori, no natural Māori object can exist without a whakapapa (genealogy).

Te Ara Tika provides no reference page, only references further reading in footnotes. Overall, there is only one quote from an external source used in Te Ara Tika. He Tangata Kei Tua and Te Mata Ira share the same references. Of the seventeen references listed in the three frameworks, two are not used at all and two are by the authors referencing themselves.

Of the remaining thirteen references, six are used only once in one general sentence, and three in another general statement of no substance. The remaining references are included as examples of projects. Overall, one external author was cited in all three frameworks.

All three publications have omitted the volumes of Māori public feedback to The Royal Commission on Genetic Modification public consultation. The feedback included a lengthy consultation process with numerous participants (Eichelbaum, 2001). The three frameworks ignore other academic research exploring a Māori view of Genetic Modification to the Royal Commission where a total of 94 individuals from multiple Iwi and regions were interviewed using kaupapa Māori research methodologies to gain results are also excluded (Leonie Pihama, Southey, & Tiakiwai, 2015). Many other consultations that Māori have made submissions on genetic issues to the Crown in the years: 1992, 1994 and 1999 have also been excluded (Hutchings & Reynolds, 2005).

Public consultations by Māori for Māori into The Royal Commission of Genetic modification in New Zealand in 2000 identified five primary tikanga (Customs): Wairua, Mauri, Tapu, Kaitiakitanga, Whakapapa (Cram, Pihama, & Barbara, 2000). Other consultations stated that the main tikanga of biotechnology are kaitiakitanga, wairua and whakapapa (Hutchings, 2004). This is consistent with other researcher’s findings including (Beaton et al., 2017); (Hutchings, 2004b); (Mead, 1996); (Mead, 1998); (Mead, 2016b); (Pihama et al., 2015) & (Cram et al., 2000). Despite these key tikanga being identified by numerous national consultations with Māori, the authors of the series of frameworks have self-identified over 40 tikanga and self-defined those tikanga with specialised meanings.

Chapter Two of the Waitangi Tribunal Wai 262 report, Ko Aotearoa Tēnei, focused on issues relating to genetic and biological resources in Taonga Species. Key sections of the chapter address topics such as: Te Ao Māori (Māori Word view) and Taonga Species (Species of cultural significance); Te Ao Pākehā (Non-Māori world view) and Research Science; Bioprospecting, Genetic Modification, and Intellectual Property; the Rights of Kaitiaki (Māori Guardian) in Taonga Species; and recommended reforms (Waitangi Tribunal, 2011).

Despite this, none of this is referenced in any of the three frameworks, nor was the tribunal report itself listed or used as a resource. Neither were conceptual frameworks that had been previously developed to assess the impact of genetics with Māori, in relation to specific biotechnologies ranging from genetically modified organisms to preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), including but not limited to (Durie, 2005); (Guyatt, McMeeking, & Tipene-Matua, 2006); (Pihama, 2001).

Te Ara Tika, as the foundation framework, in the introduction states it is “a framework for addressing Māori ethical issues within the context of decision-making by ethics committee members. It draws on a foundation of tikanga Māori (Māori protocols and practices)” (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 1). Te Ara Tika, He Tangata Kei Tua and Te Mata Ira show no proof in the writings, nor in the research and the style of writing that any kaupapa Māori (Māori Framework) methodologies were applied in their research. Te Ara Tika does list seven frameworks and in Appendix B, but no further information is provided and no kaupapa Māori frameworks and methodologies are referenced.

Consultation with selected people to seek their approval and endorsement has been a common issue with genetic research, and in fact with Māori consultations by government. “Selbourne Biological Services consulted only five individuals of a hapū and sought final approval by depicting these five people as consultation with iwi” (Mead, 1997).

The series of publications have no specific references, no whakapapa (sources) identifying the research participants, nor do the authors introduce themselves and do not identify their iwi (tribal) affiliations in direct contrast to tikanga (Māori customs) and te Ao Māori (Māori world view).

In te Ao Māori, whakapapa (genealogy) interconnects everything from the living to the dead, to all-natural objects and to everything Māori, as a people participate in within life. It is polite and common that Māori identify themselves when in person and with their writings. Researchers who cannot or do not identify the whakapapa (genealogy) of their sources or their own whakapapa have no authority to speak about or make recommendations about taonga (valuable information) and whakapapa (genealogy). This is equally applicable on the marae as it is anywhere in society that whakapapa Māori (Māori genealogy) is discussed.

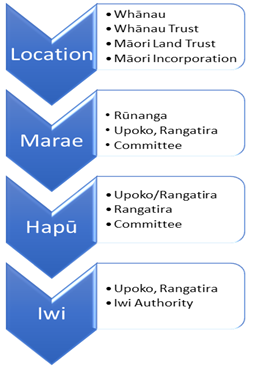

Te Ara Tika provides no definition of what an Iwi (tribal) consultation is. Some of the groups referenced as having been consulted in a footnote are incorrectly called iwi as opposed to hapū (sub clan) or whānau (family). By consulting some hapū ignores a Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview) perspective of whakapapa and Māori societal structure. Further investigation of the research participants show that those interviewed appear to whakapapa directly to the researchers which makes the research out-puts conflicted as they may not be neutral or were obtained by casual conversations.

Te Ara Tika states that “Southern Rūnaka o Ngāi Tahu were consulted”. This term ‘Rūnaka’ is ambiguous and does not clearly state who was involved. A Rūnaka is a modern corporate structure that merged hapū into a region as part of the Treaty negotiations and settlement. Each rūnaka have their own tikanga and kawa (local protocols). It is not clear who ‘Southern Rūnaka’ are, whether they are south of Kaikōura in the northern most Ngāi Tahu Rūnaka or south of Ōraka Aparima the third southernmost rūnaka and how many people were and using what kawa and tikanga. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (Tribal Corporation) estimate that less than ten percent of people with whakapapa to a rūnanga participate with their own rūnanga. “It is only the most influential whānau (families) who are participants at rūnanga whose voice and decisions are heard” (Prendergast-Tarena, 2015).

Te Ao Māori Perspectives

This section analyses and compares the myriad of tikanga terms and other Māori language sayings to compare how accurate and understandable they will likely be with Māori language speakers and Māori communities. Terms in the publications are cross referenced using authoritative Māori dictionaries, tikanga and mātauranga (knowledge) Māori literature.

Comparative analysis of Tikanga terms and their definitions

Mead (2016) states “the underlying principle of tikanga is cosmology”. “The primary indigenous reference for Māori values and ethics are the creation stories which highlight specific relationships deemed fundamental to the sustainability of life” and specifically for research with genetic data (Roberts et al., 2004). Cooper (2012) introduces a new Māori framework using traditional Māori stories and cosmology, in particular the story of Māui and Tāwhaki as an analysis of science shortfalls for Māori and a way to address them.

Te Ara Tika does not include any Māori cosmology, despite stating the literature is based on Te Ao Māori and tikanga. The notion of creation stories to explain concepts of tikanga is mentioned only once, but not applied or explained in He Tangata Kei Tua (Hudson, Russell, et al., 2016, p. 2). No further explanation or cosmology stories, nor how cosmology relates to genomics appears in the series.

All three frameworks contain a glossary with the following disclaimer “Disclaimer: Many of the descriptions used in this glossary are specific interpretations for the purposes of this document and do not denote the fullness of meaning normally associated with the word or term (Hudson, Beaton, et al., 2016a, 2016b; Hudson et al., 2010)”. Such a disclaimer prevents Māori language speakers and Māori cultural practitioners from being able to interpret the meanings and terms if applied by ethical researchers. It is reminiscent of the different texts of Te Tiriti o Waitangi with the Treaty of Waitangi. It will furthermore complicate the Māori perspectives and will only create confusion and mistrust by Māori to the researchers when they are using Māori terms that are not properly understood or misquoted.

“From early missionary time onwards, words referring to Māori epistemology and epistemological ideas were translated with English words that refer to Western religious beliefs and practices – atua as ‘god (rather than powerful ancestor) and wairua as ‘spirit’ (rather than a person’s immaterial being); tapu as ‘sacred’, rather than ancestral presence; noa as ‘profane’, instead of ancestral absence’; tohunga as priest rather than expert; karakia as ‘prayer’, instead of chant; and Tangaroa, Tāne, Tāwhiri-mātea as the ‘gods’ of the sea, forest, and winds, instead of these ancestral beings in all of their power” (Salmond, 2017).

The following table analyses ten of the tikanga which represent about one quarter of the terms used in the glossaries to use as an example of the usage and obfuscation of the tikanga terms.

The following list analyses ten of the tikanga which represent about one quarter of the terms used in the glossaries to use as an example of the usage and obfuscation of the tikanga terms.

Aroha

“Faith and Care: (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 6).

Benton 2013 states that “This word conveys the ideas of overwhelming feeling, pity, affectionate and passionate yearning, personal warmth towards another, compassion and empath, originally especially in the context of strong bonds to people and places. Its meaning was considerably widened (and to some extent diluted) after contact with Christianity and Euro-American influences, to also embrace charity in a more universal sense and romantic love of all kinds” (Richard Benton et al., 2013).

2. Williams Māori Dictionary has the following descriptions: “Love, yearning; Pity, compassion; Affectionate regard; Feel love or pity; Show approval” (H. W. Williams, 1957).

Kaitiakitanga and Kaitiaki

“Brave, competent and capable, best practice, guardian/advocate” (Hudson et al., 2010); (Hudson, Beaton, et al., 2016a, p. 26); (Hudson, Beaton, et al., 2016b, p. 25).

In recent times, Kaitiaki has become a common term used by bureaucrats in environmental policies and in legislation. Upoko of Ngāi Tahu Rūnanga Ngāi Tūāhuriri states that “Kaitiaki is a term used with such irregularity that it is now meaningless. Today, kaitiaki is a term used by Māori and Pākehā bureaucrats as a gap-filler to mean everything and yet nothing” (Tau, 2017, p. 15). Benton states that “the modern usage of the word has come to encapsulate an emerging ethic of guardianship or trusteeship especially over natural resources” (Benton et al., 2013).

2. Barlow states that “Kaitiaki or guardian are left behind by deceased ancestors to watch over their descendants and to protect sacred places”. Kaitiaki are also messengers and a means of communication between the spirit realm and the human world. Kaitiaki can be in the form of birds, insects, animals, and fish. Many kaumātua act as guardians of the sea, rivers, lands, forests, family and marae” (Barlow, 1991, p. 41).

3. The term tiaki, whilst its basic meaning is ‘to guard’ has other closely related meanings depending on the context. Tiaki may therefore also mean, to keep, to preserve, to conserve, to foster, to protect, to shelter, to keep watch over.

4. The prefix kai with a verb denotes the agent of the act. A kaitiaki is a guardian, keeper, preserver, conservator, foster-parent, protector. The suffix tanga, when added to the noun, transforms the term to mean guardianship, preservation, conservation, fostering, protecting, sheltering.

5. Kaitiakitanga is defined in the Resource Management Act as “guardianship and/or stewardship. Stewardship is not an appropriate definition since the original English meaning of Stewardship is ‘to guard someone else’s property’. Apart from having overtones of a master-servant relationship, ownership of property in the pre-contact period was a foreign concept. The closest idea to ownership was that of the private use of a limited number of personal things such as garments, combs, and weapons. Apart from this, all other use of land, waters, forests, fisheries were a communal and or Iwi right. All-natural resources, all life was birthed from Papatūānuku. Thus, the resources of the earth did not belong to man, but rather man belonged to the earth. Kaitiakitanga and Rangatiratanga are intimately linked” (Marsden & Henare, 1992).

Kawa

Primary values, principles (Hudson et al., 2010).

“A class of karakia, or ceremonies in connection with a new house or canoe, the birth of a child, a battle, etc”. (Williams, 1957). In addition to the ceremony Williams stated, “in modern usage, the term often indicates the protocol governing ceremonial conduct on a particular marae and in formal contacts between social groups”.

Rohe pōtae

Used to define the term Tribal area (Hudson et al., 2010).

The complete and correct term is ‘Te Rohe Pōtae’ which is best known as applying to the King Country. It was also used elsewhere to mean autonomous Māori land. “Te Rohe Pōtae o Tūhoe’ referred to Tūhoe tribal land beyond a confiscation line in the eastern Bay of Plenty in the late 1860s” in Tūranganui (Gisborne). Māori also spoke of the concept in the 1850s. The head is sacred to Māori, and the idea that the ‘pōtae’ (hat) “related to authority over land was derived from the “crown worn by Queen Victoria – one of the symbols of her authority” (Pollock, 2015).

Taonga

Resources (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 19).

“A socially or culturally valuable object, resource or technique, phenomenon or idea” (Benton et al., 2013, p. 396). 2. Refers to a “wide range of valuable possessions and attributes, concrete and abstract” (Biggs, 1989, p. 140).

Tapu

Restricted (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 4).

“A key concept in Polynesian philosophy and religion, denoting the intersection between the human and the divine. Used as a term to indicate states of restriction and prohibition whose violation, often included the death of the violator and others involved, directly or indirectly. “Its specific meanings include “sacred”, under ritual restriction, prohibited” (Benton et al., 2013, p. 404). 2. Under religious or superstitious “restriction; “Beyond one’s power, inaccessible; Sacred (mod); Ceremonial restriction, quality or condition of being subject to such restriction (Williams, 1971). 3. From a purely legal aspect, it suggests a contractual relationship has been made between the individual and deity.

Te Ao Māori

Māori world (Hudson et al., 2010).

“The Māori world view (te ao Māori) acknowledges the interconnectedness and interrelationship of all living & non-living things in the physical, psychological, theological, and spiritual realms. 2. Māori worldview lies at the very heart of Māori culture – touching, interacting with, and strongly influencing every aspect of the culture. This contributes to the Māori holistic view of the world and the Māori place in it” (M. o. Marsden & Royal, 2003, pp. 19,20). 3. “Māori beliefs, custom, and values are derived from a mixture of cosmogony, cosmology, mythology, religion, and anthropology” (Best, 1924b); (Buck, 1949); (Biggs & Barlow, 1990); (Marsden & Henare, 1992); (Mead, 2003)

Tohunga

cultural experts (Hudson, Beaton, et al., 2016a, p. 15).

1. “An expert in any branch of knowledge, religious or secular, and a skilled practitioner of an art or craft. It includes (but is not limited to) those whose function primarily ritual and priestly” (Benton, 2012, p. 434).2. Is often translated as ‘expert’. “Such use is wrong. Tohunga is the gerundive of tohu and means ‘a chosen one’ or appointed one” (Marsden & Royal, 2003, p. 14).

Whakapono

Faith (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 19).

The definition stated in He Ara Tika are scriptural translations from Paipera Tapu (Bible Society New Zealand, 2012). “Pono was consistently to convey the Hebrew ‘mn’ belief in adherence to an idea or set of principles and its derivatives, generally translated into English as ‘faithful, faithfulness, faith believe, truth” (Benton et al., 2013). 2. The traditional meaning of ‘pono’ is: “absolutely true; genuine; unfeigned” (Benton et al., 2013).

Analysis of Whakataukī

A whakataukī is also known synonymously as whakatauakī and pepeha.

“A whakataukī is a concise, formulaic saying, such as a proverb, aphorism, short karakia (prayer), or memorable, witty remark. It is used especially (but by no means exclusively) for sayings that encapsulate the boundaries or tribal group or region. By extension, this word can also be used as a general term for a “figure of speech, and as a verb can mean either to make such a remark, or to boast about some accomplishment, or intended action. A whakataukī is used to express customary ideas” (Benton et al., 2013).

Hirini Mead (2016) comments that “whakataukī are not merely historical relics. “Rather they constitute a communication with the ancestors. Through the medium of the words, it is possible to discover how they thought about life and its problems. Their advice is as valuable today as it was before”.

Sir Hirini Moko Mead further describes a whakataukī as “It’s a very succinct message which places a high value on a certain aspect of human behaviour. These are stated as universal truths that people need to be aware of, and that people need to use to guide their behaviour and also to guide their judgements about what to say and what not to say and what to do, and what not to do” (Mead, 2016a).

Sir Apirana Ngata emphasized the importance of using the correct version and context of a whakataukī to avoid misinterpretations and misunderstandings which are common with uninformed translations (Ngata, Buck, & Sorrenson, 1986).

Kia aroha ki a Tangaroa

This is translated by the authors of Te Ara Tika as “to be careful and aware of the potential dangers in the sea” (Hudson et al., 2010). Then it appears with a different translation in the glossary where it is defined as “In a traditional context, a person going fishing, or diving might be cautioned with the phrase ‘to be careful and aware of the potential dangers in the sea”.

The subject of the whakataukī is “Tangaroa”. Tangaroa is the deity of the sea/ocean and progenitor of fish (Mead & Grove, 2001). A more correct translation could read “Be respectful of the practices and knowledge of Tangaroa the god of the ocean and ensure you pray and offer thanks to Tangaroa”.

“Very great reverence is paid to Tangaroa by Māori when engaged in fishing, and on no account is cooked food allowed to be taken in the canoe at such times, and even old pipes are forbidden” (Gudgeon, 1905). It is custom to always say a karakia (prayer) to Tangaroa and Ikatere (Deity of fish) among other Māori deity when fishing and taking food from the ocean. It is also appropriate to offer back to Tangaroa some of the days catch. Strict observances are made by people who take fish from the ocean as to where they will shell and fillet the fish and place the leftovers. “Tangaroa will be angry and will not allow you to have a plentiful fishing trip if you eat or prepare food form the ocean too close to the ocean” (Edwards, 1990).

The most common and universal Māori word and root word for ‘ocean’ and ‘sea’ is moana (Biggs, 1981; Cormack, 1995; Moorfield, 2011; Ryan, 2012; Sinclair & Calman, 2012; Strickland & Fisheries, 1990; Tauroa, 2006; Tregear, 2014; Williams, 1975).

Tangaroa is the common Māori word for the Atua of the ocean and does not have any other definitions applied to the term (Moorfield, 2011; Tregear, 2014; Williams, 1992).

Kei tua i te awe mapara, he tangata ke. Mana e noho te ao nei—he ma

He Tangata kei ua translates this as “Who makes the decisions after consent has been given?”.

Sir Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hīroa) translates and discusses the meaning of the whakataukī which differs greatly from the literature. The meaning is about the Māori population being interbred and losing their customs (Buck, 1949, p. 537). The whakataukī is not related to the definition provided by the authors of the literature.

Me ātahaere mā ngā ngaru, kei tōtohu i te aroha o Tangaroa

Te Mata Ira states this whakataukī that is used as a guiding principle and translates it as “Tread carefully in challenging waters”.

Combining the words āta and haere together is linguistically incorrect (Te Taura Whiri I te Reo Māori, 2012). Again, as in the previous example, the subject is Tangaroa the deity of the ocean and this is further reinforced by the use of the word “o” stating of a superior being. The whakataukī is confusing to understand and does not translate to the definition provided by the authors. A more appropriate whakataukī could have been found in Māori epistemology or in the authoritative Ngā Pēpeha o ngā Tipuna (Grove, 1985, pp. 89, 182, 381).

Kanohi ki kanohi

This whakataukī is referenced four times in Te Ara Tika, including in the Glossary. The only explanation provided is a direct translation “face to face”. The meaning of this whakataukī implies that if correct contact must be made then people should meet face to face, one on one, so that no misunderstandings, misconstruing, misinterpretations, misapprehensions, misconstructions can occur. This term is commonly used in everyday language by Māori language speakers. A more careful analysis of the statement is that it implies that “by taking the time and energy to arrange and travel to meet somebody you are showing the respect and homage that this person is worthy of your efforts” (Keegan, 2000).

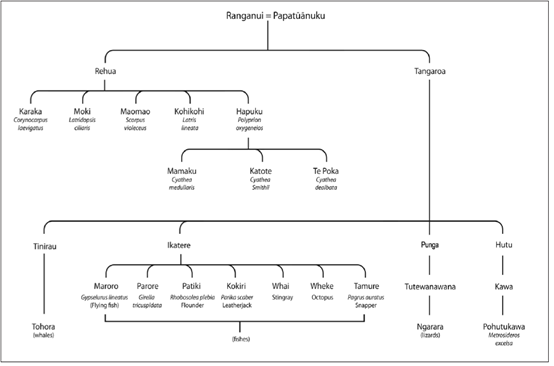

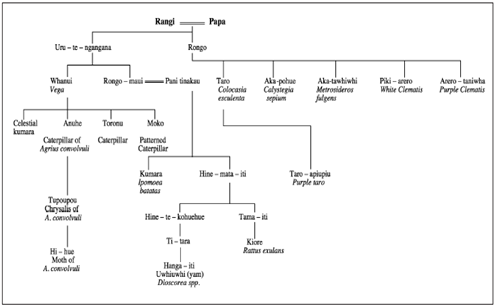

Ira tangata as Taonga Species

Epistemology and Whakapapa Māori with many Iwi states that Māori human beings are the youngest of the children of Tāne Māhuta, the father of all the birds, insects, and all other living forest species. Tāne Māhuta also created the first human being with Hine Ahu-one. A Te Ao Māori perspective is that there is no difference with human and non-human species genetic materials as all species are closely related by whakapapa. Humans are the kaitiaki for all other species and all other species are the kaitiaki of human beings.

If Te Ara Tika, He Tangata Kei Tua and Te Mata Ira were based on Te Ao Māori and tikanga as they state, the ethical guidelines would be written for all species as one set of species cannot be separated from another with ethical consideration of Māori genetic and genomic research.

Traditional Māori knowledge has a story that reminds us of the dangers of ignoring or thinking that non-human species are not as important as human species.

“When Māui entered Hine-nui-i-te-po, he began to push harder, and the little kick his feet gave made his brothers laugh, and the birds joined in. If Māui had not been cruel to the Tītwaiwaka (Fantail/Rhipidura fuliginosa), Pakura (Swamp-Turkey/Porphyrio porphyrio), and other birds he might have conquered death, but his treatment of them had made these birds angry, and they did not obey his injunctions to keep well back but pressed up quite close. The fantail came fluttering over her face, and its long tail tickled her nose and she stirred just as the brothers laughed at Māui’s wriggles. This made the fantail giggle, and the other birds joined in, and the sound awakened her with such dire results to Māui that he never appeared again” (Tikao & Beattie, 1939, pp. 32-33).

Indigenous and International instruments

There are a number of specific treaties and declarations that bind Māori and the Crown to respect ethical considerations of biological research of Māori genetic data. There are also a number of international instruments that should be considered when writing about Māori ethics with genetic research.

He W[h]akaputanga

He W[h]akaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni is also known as the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand. “Translated, it can mean ‘an emergence’, referring to the birth of a new nation, Nu Tireni – New Zealand – but also marking steps towards unified forms of governance among the many different rangatira and their hapū and iwi” (Waitangi Tribunal, 2014, pp. 153-154).

He Whakaputanga is not mentioned in any of the frameworks, despite being a nationally significant declaration between Māori and the British (Waitangi Tribunal, 2014). He Whakaputanga offers a significant amount of protection and considerations that any researcher with Māori genetic materials should be aware of. “He Whakaputanga has often been considered no more than a minor prelude on the journey to the Treaty of Waitangi” (Waitangi Tribunal, 2014, p. 195).

“Yet such a viewpoint considerably undersells He Whakaputanga. For one thing, it was British acknowledgement of the validity of the Declaration of Independence that made it necessary to seek a cession of sovereignty when the British government decided to intervene further in New Zealand in 1839. The Crown had recognised the sovereign authority of the United Tribes of New Zealand and would need the agreement of those rangatira in order to alter that situation” (Kawharu, 1989, p. 130).

For many Māori, the Treaty did not, and could not, erase the clear assertion of rangatiratanga – chiefly authority or sovereignty – made through He Whakaputanga. For that reason and others, He Whakaputanga “remains a taonga of great significance today He Whakaputanga was – and remains – proof that the rangatiratanga and mana of Māori had been clearly articulated and asserted. New Zealand had been a sovereign land under the authority of the united tribes before 1840; and, according to the Waitangi Tribunal, that sovereignty was not extinguished by the Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty itself was another step in the ever-deepening alliance or covenant with Britain” (O’Malley & Harris, 2017).

Article I of He Whakaputanga state that the crown will honour its obligations to the tribes who were signatories and that these tribes would not be subjected to the current laws and bio piracy that Māori have endured for decades. While Article II gives the signatories the right to practice their own kaitiakitanga with Māori genetic data. It could have been possible that a Māori genetic data academy and a government office would already have been established to protect Māori. Article III is an agreement that a congress would meet in autumn each year to make laws and decisions that impact on Māori Peoples. This could have also led to a set of ethics being created and legislated to protect Māori.

Te Tiriti

“A treaty is a legally binding international instrument agreed to and signed by two or more sovereign nations. All parties to a treaty are required to abide by its provisions unless they abrogate” (formally withdraw from it) (Healy & Huygens, 2015).

Despite Te Ara Tika stating that the Treaty of Waitangi is one of the strands it is based upon, none of the framework’s references or discusses Te Tiriti. In direct contradiction of Te Ao Māori values and Tikanga, Article II of the Treaty of Waitangi is mentioned several times in Te Ara Tika with no meaningful discussion. Te Ara Tika ignores the Preamble and all three Articles of Te Tiriti and the three principles which are applicable to genetic and genomic research.

The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. The Treaty of Waitangi has texts: one in te reo Māori and one in English. The Māori text is referred to as Te Tiriti o Waitangi and is not an exact translation of the English text called The Treaty of Waitangi. These differences, coupled with the need to apply the Treaty in contemporary circumstances, led Parliament to refer to the principles of the Treaty in legislation, rather than to the Treaty texts. It is the principles, therefore, that the Courts have considered when interpreting legislative references to the Treaty (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2001)

Te Tiriti affords Māori the rights to protection of rangatiratanga (chiefly autonomy or authority over their own whenua (land) and taonga (treasured resources and possessions). Māori genetic resources are a taonga as it is the foundation of all whakapapa Māori. The frameworks use the term whakapapa, but it is used to describe relationships with researchers as opposed to its correct meaning of genealogy and the Māori view of genetic materials, therefore the rights of protection are not recognised.

It is essential that in order to recognise and discuss anything about Māori biological materials and their ownership that Te Tiriti be included and that these principles are observed and respected in good faith. By using the treaty principles will ensure that researchers, Māori Peoples, whānau, hapū and Iwi engage in dialogue about Māori concerns and rights.

The Principle of Active protection

“The Tribunal has elaborated the principle of protection as part of its understanding of the exchange of sovereignty for the protection of rangatiratanga and has explicitly referred to the Crown’s obligation to protect Māori capacity to retain tribal authority over tribal affairs, and to live according to their cultural preferences. Later Tribunal reports also place emphasis on the Crown’s duty to protect Māori as a people, and as individuals, in addition to protecting their property and culture” (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2001). This is applicable to Māori and genetic and genomic research as this thesis will explain that DNA and any body fluids are tapu. There is a myriad of tikanga and traditional values that must be considered by researchers when accessing and analysing genetic and genomic research.

The Principle of Redress

“The Court of Appeal has acknowledged that it is a principle of partnership generally, and of the Treaty relationship in particular, that past wrongs give rise to a right of redress. This acknowledgment is in keeping with the fiduciary obligations inherent in the Treaty partnership” (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2001). This thesis explains why and how Māori genetic data is a taonga. Ethics and the Crown need to consider this within all legislation and decision-making processes that encompass Māori genetic data. While article III promises to Māori equal rights by the Crown. Currently Māori rights are being ignored and the fact that Māori genetic data is a taonga is also being ignored.

The Principle of Partnership

“Both the Courts and the Waitangi Tribunal frequently refer to the concept of partnership to describe the relationship between the Crown and Māori. Partnership can be usefully regarded as an overarching tenet, from which other key principles have been derived” (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2001). This inherent right creates a new category of Māori rights, Genetic Data Sovereignty. Māori, whānau, hapū and Iwi have the right to govern and manage their own genetic data.

Other binding and guiding instruments to New Zealand

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) recognises Māori rights to their culture, beliefs, and ownership of genetic materials. It is a significant instrument protecting Māori rights and in addition to Te Tiriti and He Whakaputanga with both documents forming the moral basis for any Māori ethics. Despite this, UNDRIP is mentioned in one sentence in Te Ara Tika, with a footnote to a web site. There is no explanation of how to integrate and understand the relevance of the Declaration with ethical research of Māori genetic materials.

Despite numerous Acts of Parliament that directly impact Māori and their genetic materials including Patents Act 1953; The Criminal Investigations (Bodily Samples) Act 1995, Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996; Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (HART) Act 2004; Guthrie Cards Public Health Bill 177-1 (2007), none of these were included or mentioned in any of the three frameworks.

International Instruments

The Pacific Islands Indigenous Peoples who have very similar cultures and beliefs to Māori and have been combatting unethical usage of their genetic materials by creating declarations regarding exploitation of gene research, gene modification and Intellectual Property Rights of gene research. The Pacific have more than 5 treaties and declarations that are not mentioned in the frameworks. See Appendix D.

Globally, there are more than 12 international Indigenous declarations to protect Indigenous genetic data from more than 150 Indigenous Peoples and countries. See Appendix E. None are included in the frameworks

The United Nations have 8 instruments. See Appendix F. The only instrument mentioned in the frameworks is the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights 2005, which is mentioned but not explained. Te Ara Tika mentions several other international codes of ethics with no further explanation including Nuremburg Code 1947; Helsinki Declaration 1964; Belmont Report 1979; (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 1).

Conclusion

The three reviewed frameworks have highlighted the problem that mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) is neither defined nor taught as a discipline in mainstream education facilities. This creates and allows a free licence by researchers to create as they see fit. This new framework has identified and rectified the lack of Māori cultural beliefs and has provided solutions.

This review reinforces Te Maire Tau’s statement that “it is far better to anchor Māori students in Māori epistemology first before they apply extrinsic disciplines to it” (Tau, 2001, p. 72). The literature review also highlights the issues that the mainstream tertiary institutions need to ask themselves whether they can deal with Māori perceptions of the world adequately.

“It is naive to say in tertiary institutions that there is a ‘Māori dimension’ to history, education, geography, or any other discipline. To do so imposes one framework of knowledge upon another that orders itself differently” (Tau, 2001, p. 65).

“Mātauranga Māori needs to be accepted as having both a secular and a theological sense” (Te Maire Tau, 2001, p. 67). The fundamental principles of tikanga Māori are epistemology and cosmology. Despite this, Te Ara Tika, He Tangata Kei Tua and Te Mata Ira ignore Māori epistemologies reflecting the practices of the early missionaries to deflect traditional meanings. The reviewed frameworks have created confusion and obfuscation by discretely imposing western perspectives that ignore Māori customary beliefs and cultural values.

“You can never have a complete grasp of mātauranga Māori without a solid understanding of the language” (Tau, 2001, p. 68). The incorrect usage of the Māori language terms describing tikanga and whakataukī translations veil their true meanings and intentions reflecting ignorance of traditional Māori customary rights and knowledge contradicting a Te Ao Māori perspective. The impact of using incorrect Māori language could have irreversible damage to the multiple generations of people who are Māori language speakers including the Kura Kaupapa Māori schools who had just over 6,000 graduates in 2012 (Calman, 2012). Also, to the more than 152,000 Māori school children in mainstream schools who are leaning te reo Māori 2019 [8].

To present and research a taonga and a whakapapa requires decolonised research methodologies be applied to the research. Absent from all of the literature is any proof that any kaupapa Māori research methodologies and or frameworks were applied at any stage.

Despite New Zealand having two founding documents that were created between the Crown and Māori that set the genesis for any ethical discussions about Māori, the reviewed frameworks are wanting of any citations and references to those instruments. Despite there being a myriad of international, UN and Indigenous instruments that share Māori ethical beliefs and concerns, none were utilised in any of the three frameworks.

Te Ara Tika, He Tangata Kei Tua and Te Mata Ira do not represent a Te Ao Māori or tikanga Māori perspective. The result is that there is a large void of Te Ao Māori knowledge and mātauranga Māori that can be used to guide ethical decisions with Māori gene research and to guide the protection of Māori rights with Māori gene research that has not yet been published.

The development of guidelines for handling samples and specimens collected for research involving Maori Background & Research Involving Maori Guidelines for Disposal or Retention of Samples and Specimens

Found in ‘The New Zealand Medical Journal Vol 120 No 1264, pages 117-119’ in an article called ‘The development of guidelines for handling samples and specimens collected for research involving Maori [sic]’ (Cunningham et al., 2007). This literature is the basis for the internal ethical guidelines for Otago University Christchurch ‘Rangahau e pa ana ki te Maori [sic] Nga [sic] ahuatanga [sic] mo [sic] te whakakahore me te pupuri i nga [sic] tauira me nga [sic] kowaewae Research Involving Maori [sic] Guidelines for Disposal or Retention of Samples and Specimens (2007)[9]’.

The inclusion of [sic] is used as the ability to technically write macrons was widely available in 2007. As early as at least 2002, Te Taura Whiri I te Reo Māori – The Māori Language Commission has made public their ‘Māori Orthographic Conventions’ recommending they be observed by writers and editors of Māori language texts[10]. The Commission stated ‘it is essential for the survival of the language that a standardised written form be adopted by all those involved in the production of material in Māori, in order that a high-quality literary base may be built up as a resource for the Māori language learners of today and of the future. The primary recommendation that macrons are used to distinguish vowel length”.

These two guidelines being reviewed are still used as late as early 2022 at the University of Otago Christchurch with knowledge of the contents of this review provided in early 2021.

The introduction contains the following statement regarding the guidelines “to ensure consistency with cultural practices and beliefs and enhance the cultural safety of Māori participating in research”. The authors who are the Māori Research Committee are a mixture of Māori and non-Māori and non-researchers, despite the fact that the guidelines are about the sacred topic of whakapapa Māori. There is also no mention of any tikanga terms that were also being widely spoken about in Māori communities and academia at the time of publication (see previous review).

Te Tiriti/Treaty of Waitangi

The second paragraph of the literature states that the University has a commitment to ‘The Treaty of Waitangi’. Noting that this is the English version that Māori did not debate, agree to or sign. The Waitangi Tribunal have stated that the Māori language version ‘Te Tiriti’ is the authoritative version that the tribunal follows. It is important to note here, that it is often stated by Māori academics and activists “The Treaty of Waitangi undermines ‘Te Tiriti’.

He Whakaputanga is not mentioned in the literature, despite being a constitutional document for Māori and The Crown. Though Ngāi Tahu did not sign He Whakaputanga, manawhenua of Otago University in Christchurch do have a special relationship with He Whakaputanga, with the English version of the flag being displayed in the marae in Tuahiwi.

The Mataatua Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples was signed in 1993, it is not mentioned in the literature.

As with the precious reviews, the many public consultations and literature of the time regarding Māori and biological samples are also not considered.

Consultation

The stated consultation process ignores the local iwi Ngāi Tahu and its governance. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (Te Rūnanga), the tribal council, was established by the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Act 1996 to be the tribal servant, protecting, and advancing the collective interests of the iwi. The 18 Papatipu Rūnanga have their own autonomy and form the tribal council. Within the Canterbury region alone, there are eight Papatipu Rūnanga who are identified as stakeholders in the University MOU.

The consultation that did occur was with a health committee that represents seven of the Papatipu Rūnanga in Canterbury, despite the literature being about whakapapa, tikanga and mātauranga.

A common issue with non-Māori and researchers is thinking that a person of Māori descent is an expert in all things Māori. The committee are health experts and representatives who were appointed to identify and work with the Christchurch District Health Board in regard to racism and inequities Ngāi Tahu whānau faced in the health system. They are not the knowledge holders of tikanga Māori and are not kaumātua. This form of consultation was discussed in the previous literature review.

The rūnanga are referenced as ‘rūnaka’ despite many of the rūnanga not using the dialectal identifier of replacing a ‘ng’ sound with ‘k’. Any meaningful engagement with Papatipu Rūnanga must occur with the rūnanga, not standalone committees.

Karakia

It is widely accepted and published by Indigenous Peoples Communities and Indigenous Scholars that Christianity has been the vehicle of colonisation for every Indigenous Peoples group. The late Professor Ranginui Walker stated “You cannot have colonisation without Christianity”. Dr Moana Jackson who spent a life time fighting against colonisation refused, in his pre-planned tangi, to have any Christian karakia.

For an in-depth analysis of what ‘Karakia’ is and the colonial practices that have made the term simply mean ‘prayer’ is in a paper I wrote titled ‘Karakia or cultural appropriation “[11].

Any part of the human body is sacred and contains whakapapa including a deity of each part of the human body. Anyone who handles whakapapa must respect Māori tikanga and associated traditional practices. Despite these broad Māori societal beliefs, the literature in review introduces recommendations that Christian practices and beliefs are used to dispose of biological samples.

Stating that a karakia would be performed over a sample would imply that Māori cultural values are being considered and practiced. Instead, the guidelines state that a karakia was composed by an Anglican Bishop and it is recited inside a chapel that was in attendance by a number of Māori Chaplains, and that the karakia was available to both Māori and non-Māori. The Mackenzie Cancer Research Group also state this ceremony is performed in the chapel[12].

This is essentially a Christian service using te Reo Māori and is another form of colonisation on the dead and individuals who provided their whakapapa (biological sample) to the University of Otago in Christchurch. This is disrespectful to any Māori who is not Christian. It ignores the fact that more than 2 million New Zealanders have no religion and that more than 56,000 Māori identify to Ringatu and Ratana[13], Hauhau etc.

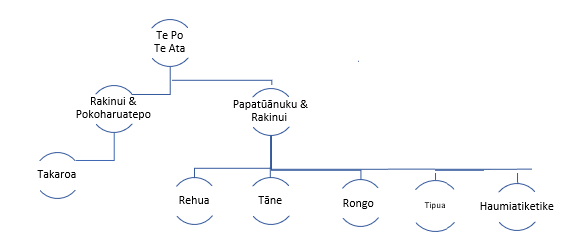

Proposed Label

The guidelines state that a distinctive label should be used to identify the sample that is to have a karakia and disposal process. While the Medical Journal does not have the label, the University of Otago created internal guidelines does.

Section 5 of the internal Guidelines state:

“Sample to be disposed of with appropriate karakia (blessing): all tubes or containers holding these samples should be identified at the time of collection with a special identification sticker using the following design (this design may be copied from this document and pasted into a file for printing tube labels or the gif file for the design can be downloaded from: http://whakaahua.maori.org.nz/kowhai.htm or contact the Research Office).”

The web site is no longer available, but still viewable in the Web Archive [14].

The label being referenced in the guidelines is in black and white. Included below are both copies from the guidelines and the web site.

For anyone who is familiar with Māori art, the image is obviously a Puhoro design. On the original web site, it is also labelled a ‘Puhoro’ by the late artist Kamera Raharaha (Te Aupouri) who owned and managed the web site ‘maori.org.nz’.

Digitised and coloured label sourced from http://www.maori.org.nz/

Otago University Christchurch label

Traditionally puhoro was reserved for the warriors and leaders who had acquired speed, agility, and swiftness. The Puhoro is a tattoo from above the waist of usually a male, to his leg, including the buttocks. The Tohunga Suppression Act and colonial attitudes towards traditional Māori tattoos nearly saw the artform die out before experiencing a renaissance in the 1990s.

Apart from the cultural misappropriation, it is totally inappropriate for a male warrior’s buttocks to be associated with a biological sample that is intended to assist others live better lives and contribute their sacred sample to health research. Showing of the buttocks in Māori culture is a sign of disrespect to the person watching.

The label which was first published in A. H. Mc Lintock (Ed.). (1966). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand has a whakapapa to Te Tai Tokerau and likely from Te Aupouri. This leads to further cultural appropriation and offence to the Iwi of Te Tai Tokerau as none of the authors whakapapa to Te Tai Tokerau.

Conclusion

Inadequate Māori cultural skills within the research team, lack of consultation and non-Māori on the Māori Research Committee likely contributed to a number of key flaws in the two guidelines.

The guidelines are not Māori culture but Christian guidelines and ceremonies that use an inappropriate and appropriated Māori image and some usage of the Māori language.

It is likely such behaviour and practices will both cement the deep-rooted mistrust with health professionals and researchers, or it could create new mistrust with researchers and health professionals.

Any research about Māori biological samples must be done in a culturally sensitive and trustworthy manner with Māori who are cultural practitioners leading the design and decision-making process.

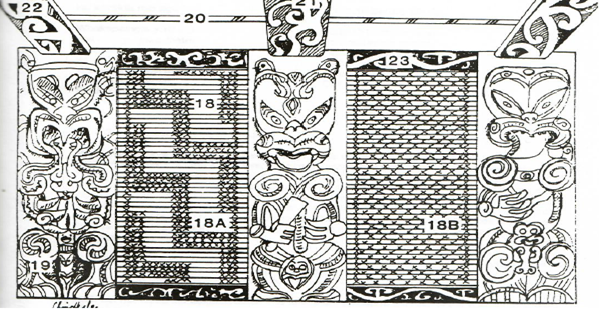

INDIGENISING DNA

Indigenising western concepts is to alter concepts so as to make it fit in with the local culture. Pre-colonial Māori knowledge was shared through many different mediums, such as pūrākau (stories), karakia (prayer), waiata (song), and “inscribed into whakairo (carvings) and raranga (woven patterns), that adorned waka (canoe), wharenui (meeting houses) and kākahu (clothes). Tā moko (tattoo) was a method of etching whakapapa (genealogy) directly onto the face of the wearer. In doing so, a face etched with tā moko expressed the story of the wearer’s life, their whakapapa, accomplishments, and triumphs as well as their status within their hapū” (Deana Walker, 2019). In the same manner as Māori shared knowledge pre-colonial times and now, this section will identify three Māori concepts to describe genetics and genomics.

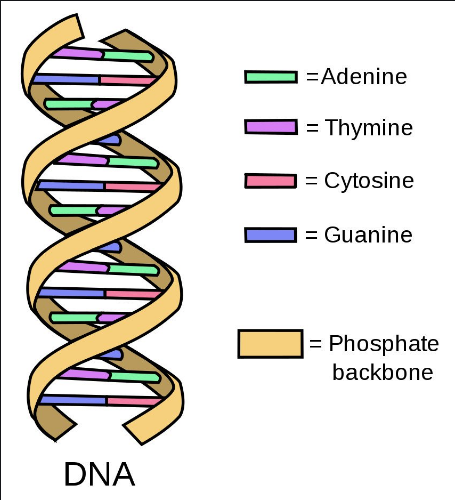

Ruatau

The interwoven form of the DNA structure is well known today. Double helix is the description of the structure of a DNA molecule. A DNA molecule consists of two strands that wind around each other like a twisted ladder. Each strand has a backbone made of alternating groups of sugar (deoxyribose) and phosphate groups. Attached to each sugar is one of four bases: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), or thymine (T). The two strands are held together by bonds between the bases, adenine forming a base pair with thymine, and cytosine forming a base pair with guanine.

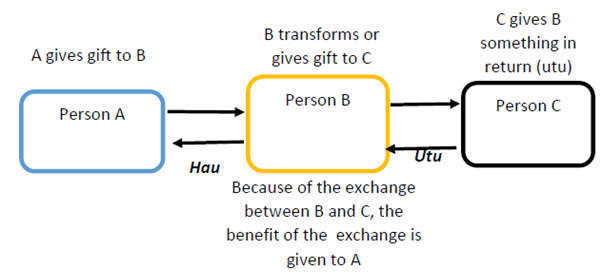

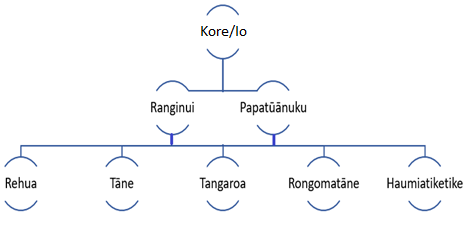

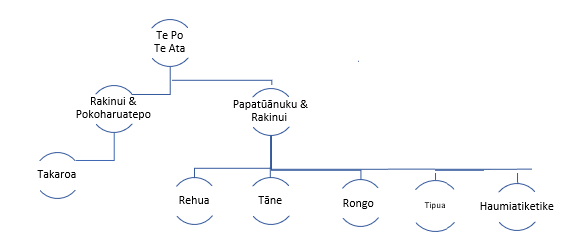

WAI 262 Claimant witness Mana Cracknell spoke of te ruatau, a dual helix formation, sometimes seen in kōwhaiwhai patterns, that represents the interwoven nature of different forms of knowledge (Waitangi Tribunal, 2011b, p. 80). The ruatau in weaving is the symbolic symbol of the atua Ruatau. In traditional knowledge among some Iwi, Rehua and Ruatau are two of the twelve whatukura or male attendants in the Māori spirit worlds. There were also twelve female attendants called Māreikura. The whatukura were messengers of Io, while the Māreikura greet the dead spirits when they enter the home of Io in the 12th spirit world known as Tikitiki-o-rangi.

Their home is called Te Rauroha. On another occasion they were sent by Io to see which of children of Ranginui and Papatūānuku would be worthy of the three baskets of knowledge. They chose Tane Māhuta the creator of humans and many other species of the forest. Whakamoeariki was the name of the house where dwelt the gods Ruatau, Aitu-pawa, Rehua, and the Pono-aua, called ‘The Many of Pono-aua (Best, 1924a, p. 36).

In an ancient karakia highlighting the relationship of ira atua and ira tangata recited during a person receiving their moko, a reference is made to Ruatau. “From Io knowledge is passed through Ruatau.” This descent from Io to Ruatau and finally to Tane-te-waiora describes how knowledge was passed down from the spirit worlds to the latter, who ultimately passed it on to humans.

Variations of Tane’s name which includes Tane-te-waiora indicating “life, prosperity, welfare, sunlight”, an appropriate term during the process of tā moko (King, M. 1973, pp. 20-22). DNA represents the relationship between the physical and the spiritual, a connection to all ancestors and atua since the beginning of time as does Ruatau.

Common DNA images are a metaphoric symbol of our human whakapapa. Our human chromosomes and genes determine our genetic makeup of individual existence. The molecule is packaged as a double stranded structure that is twisted into a helix. Similarly, the whiri whenu resembles a helix shape. They are physical manifestations of esoteric knowledge from our ancient past brought to life by the art forms of raranga and whatu muka, and all of the knowledge contained within these. This symbol is not unlike the process of miro (spin or roll together), which combines two strands of harakeke and forms a whiri (Taituha, 2014).

Whenu is a single-pair twining’ weaving technique which can be likened to Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid or DNA symbolised by the helix shape, because the living entities; each has an individual whakapapa and are unique because they are individually conceptualized and therefore carry their own story.

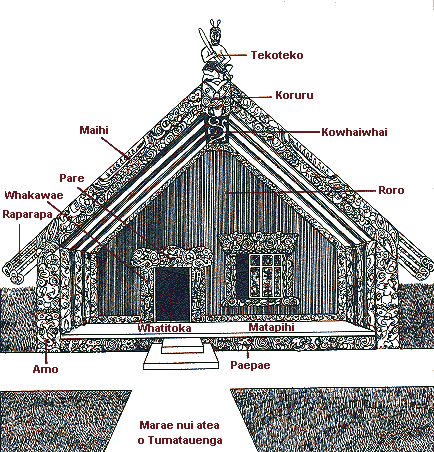

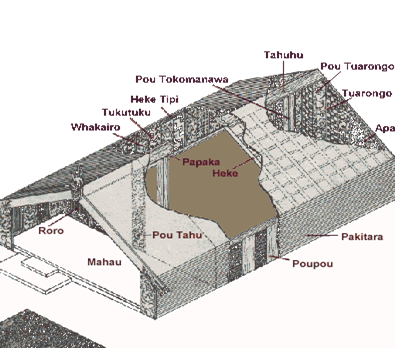

Wharenui as a genome

An original WAI 262 claimant Del Wihongi of the Ngā Puhi tribe stated a genome is a representation of a wharenui (Wihongi, H., 2019). This section analyses and extrapolates that statement, providing an indigenised account of how a wharenui represents a genome.

A wharenui has many names, including tipuna whare, whare tipuna, meeting house, marae, etc. In nearly all cases the wharenui proper is not only named after an ancestor but is a physical representation of the tribal ancestor it is named after and resembles the human body in structure.

There is a tendency to use the word ‘marae’ to mean the total complex of buildings and land. In fact, the marae is the open grassed or concrete space immediately in front of the ancestral meeting house. It is correct to use the word marae in either context, but the different meanings should be kept in mind (Richardson et al., 1988).